from diaCRITICS, the leading blog on Vietnamese and diasporic arts, culture, and politics. diacritics.org

Clik here to view.

Professor Kieu-Linh Caroline Valverde

An Interview with Kieu-Linh Caroline Valverde–scholar, activist, writer–touches upon the many journeys made in the production of her book: Transnationalizing Viet Nam: Community, Culture, and Politics in the Diaspora (Temple University Press 2012). In doing so, she recounts a life of intrepid choices and harrowing sacrifices. A life of the mind, a life consumed by art.

[Do you enjoy reading diaCRITICS? Then please consider subscribing! See the options to the above right, via email and RSS]

–

Kieu-Linh Caroline Valverde smiles at the webcam like the parent of a newborn. The release of Transnationalizing Viet Nam, a project involving twenty years of research, was a long labor. Covering a wide range of topics—pop music, internet communication, art, politics—Valverde’s study is well worth the time it took to write it. Yen Le Espiritu has called the work “a rich and nuanced study of transnational linkages between Viet Nam and its diaspora in the United States.” Indeed, this is perhaps one of the most important works on the Vietnamese diaspora in the United States in recent memory.

Valverde is no stranger to the Vietnamese American art community. She has worked closely with Association for Viet Arts and the San Jose Museum of Quilts and Texiles, curating the exhibit Áo dài: A Modern Design Coming of Age which included over 100 áo dài from Vietnam. The exhibit received national and international recognition. As a scholar and writer, her work has been published in the Journal of Asian American Studies, Amerasia Journal, and Racially Mixed People in America (edited by Maria P. P. Root). She teaches at UC Davis.

Dr. Valverde was kind enough to set aside time in the middle of the winter holidays to speak with diaCritics about her book, her research, and the role of art in Vietnamese diasporic communities.

I was really intrigued by the cover of Transnationalizing Viet Nam. It’s a picture of a man holding a flag that’s a mixture of the North Vietnamese flag and the Southern Vietnamese flag. I was wondering if you could tell me if there’s a story behind the picture.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

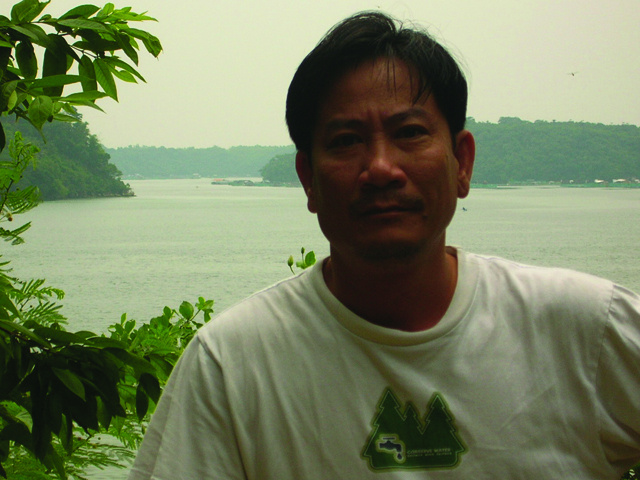

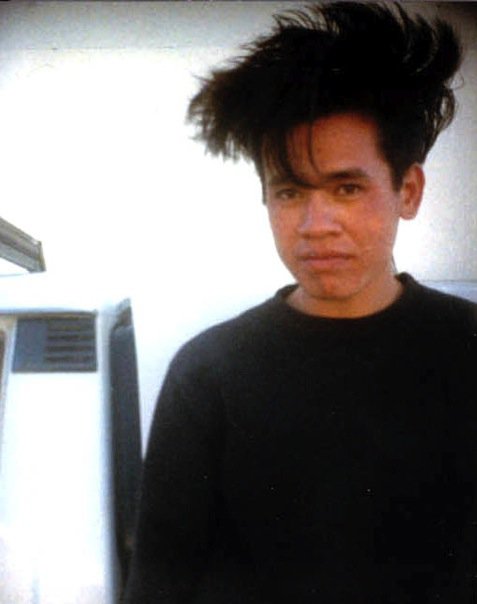

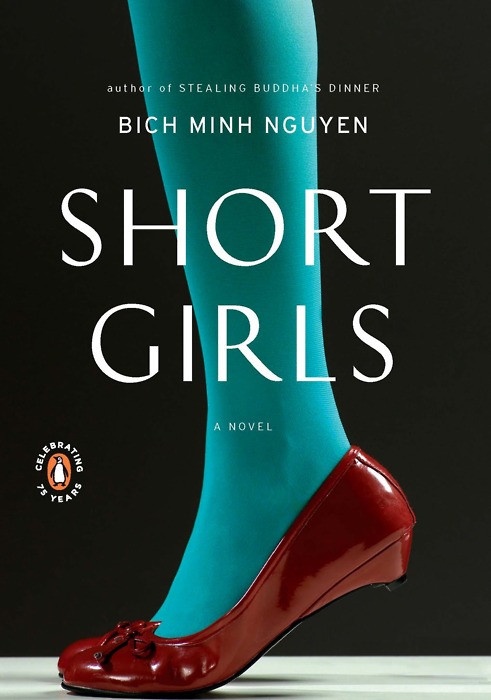

- James Du’s one-man counter-protest in support of FOB II

Absolutely! I don’t know the exact dates to be honest, maybe 2008, 2009—somewhere around there; it seems like yesterday.

It was a protest in front of an exhibit, FOB II, which was an exhibit of 50 artists from Vietnam and the United States. It was curated by Lan Duong and her co curator who were reacting to the Madison Nguyen controversy and the year-long protest of the artist Chau Huynh. As an artist, one of Huynh’s mediums was quilt and so she created this quilt of the South and North Vietnamese flag to represent a marriage quilt because she is from a communist family in Vietnam; her husband comes from a south Vietnamese family, immigrated, was part of that group that married international brides. Huynh was actually an international bride and then an MFA art student.

James Du is the person holding the flag. He bought that flag from Huynh to stage a series of one-man counter-protests against certain anti-communist groups in the community who protested based on the idea that the art exhibit had communist content. James Du, he’s holding it up defiantly and people are pointing out, “Hey, do you know there’s a communist flag there?” Within minutes of this, they started beating him up. The police came and arrested him or put him in cuffs because they said they wanted to protect him. The photo is just a really dynamic split second thing before that altercation.

That flag and that image really represent the work of my book, which is to say that overseas Vietnamese are very much informed by what goes on in the United States policy-wise and in the society, in Vietnam policy and society, but also by anticommunist groups within the community. We, as overseas Vietnamese, are very cognizant of these triple dominations or triple influences, and even though we have these influences, we still manage to create linkages to Vietnam. My book documents the ways in which we do this through arts and media and politics and technology and so forth. That’s why that image was chosen.

I think it really captures the moments in your book when you talk about the anticommunist forces within the community. Since you did a lot of field research within the Vietnamese American community, did you encounter first hand any of those anticommunist forces?

That the book stands alone as the first and still the only text that is critical of the anticommunist groups–there were some dangers in the research.

Because I’m part of the community, I was able to do the research on all sides: the staunch anticommunists, very conservative organizations, more moderate groups, as well as those who are pro-business, pro-connection with Vietnam, and in Vietnam those within the government itself who looked at the overseas population as a threat. I had the whole gamut of the political hotbed. I think maybe that’s why the book took 20 years to do because you know, you can’t exactly come in and say “Tell us why you want to kill communist sympathizers.” It is after decades of trust-building and introductions and connections that then I’m allowed to have access and the participants are able to tell me truthfully their experiences. And then I was able to be critical of these forces; I think I was a neutral researcher, but then there’s a point when it’s really clear that anticommunists—they bring a lot of fear to the community. It’s not just the general population but it’s scholars as well who have told me they’re not going to write something like this because they don’t want to have the repercussions. They don’t want to have been denied access to the community. They don’t want their parents to be upset with them, their family members to be critical. There’s a lot at stake personally, familially, politically when you engage in the kind of research and scholarship that I chose to do. It was dangerous and it is dangerous still. And I don’t know what the repercussions would be in the long term.

That chapter in your book on Madison Nguyen and the anticommunists really surprised me. For me as a second generation Vietnamese American, “Little Saigon” would just be a name, but the way you researched into it, what you presented, readers could see the little nuances to it and I found that really interesting.

Clik here to view.

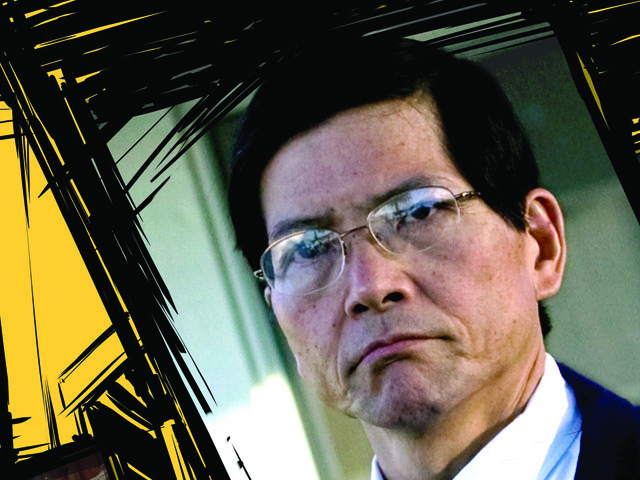

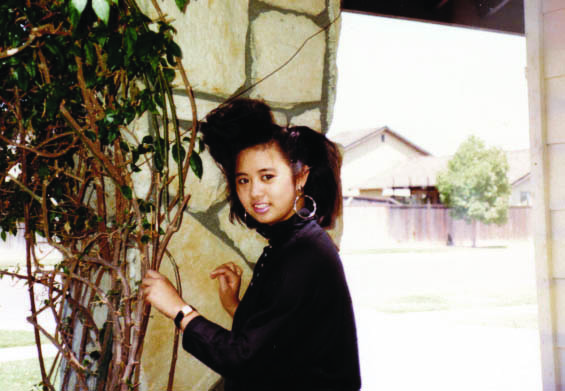

Pro Little Saigon demonstrators.

Touching on that, you’ve said you’re mixed ethnicity. Your mother is Vietnamese, Spanish, French; your father is Vietnamese English. Tell me a little bit more about how that affected your research—how did that influence you to go into this field and how has that influenced you in your fieldwork?

My original research interest was around mixed race issues, but then ultimately I would do work on the diaspora and the diaspora of Vietnam.

I have to say because I was cognizant of mixed race identity—the phenotypes, the ways in which (and I’ve written extensively about this) the community perceive a mixed race person of my generation (người lai, con lai, and all that). I was really hyper-aware of how one would perceive me, how one would perceive me with Vietnamese fluency, how one would perceive me with my gender and generation. I honestly played up a lot of that in order to negotiate spaces in order to build trust.

If I had been an older generation Vietnamese male or even a younger generation Vietnamese male or even Vietnamese female, there would have been a sense of “Maybe we can’t trust her because she’s too much a part of the community.” Or if I’m in Vietnam, they can’t trust me because I’d seem too much a part of the anticommunist diaspora. But since I sort of ride this unique space phenotypically, my language, my accent, my age, gender, I think I was able to negotiate a space where I at least appear very neutral, as neutral as I can be in a very hyper sensitive political dangerous zone.

Now how successful I was, it’s debatable. There’s a story I didn’t put in my book, I think it was 2006. I was in Hanoi and I was really proud of myself that I scored really high level interviews with ministers and so I was talking to one of my Canadian Viet Kieu friends who happened to be seeing someone at the US embassy at the time. She knew I was doing research and giving me connections. I came back and I was hanging out with her and she said, “Oh my god, I just got news that the Vietnamese government was wondering, ‘Why are you sending us this American girl who’s fluent in Vietnamese to spy on us?’” And I thought I was doing such a good job!

There are lots of stories like that, when you think you’re doing this magnificent job and then they have their own impression of who you are. I think I would rather be a white scholar from the US than a Viet Kieu, which they trust even less. At the time, it was really harrowing and frustrating but in retrospect, it’s really comical.

Because you did some of your research before 1995, before the relaxing of relations between the US and Vietnam, what challenges did you face in your pre-1995 research?

It was even worst because there was no diplomatic relations. Getting into Vietnam was difficult. The US was not that supportive of researchers going back to Vietnam and did not make it easy. Vietnam did not give out visas. I snuck into the country on a tourist visa. I was very young—I was in my early 20s—and I was really determined to do research on Vietnam. I had to pick a university that would even allow it. There were two universities in the United States—Yale and the University of Hawaii Manoa—that allowed for grad students to even go back to Vietnam and it was not even guaranteed. So I snuck into Vietnam on a tourist visa and went to my sponsoring agency and begged them to extend the visa.

There was no US embassy at the time, but there was a consulate and I came by very naively and said, “Hey, I wanted to do Viet Kieu research, what can you tell me?” And they’re like, “We’re not going to help you, don’t come to us. We’re not responsible for you, you’re just this crazy Viet Kieu academic and you’re on your own, buddy!” That kind of stuff was the reality then.

I absolutely had to be secretive with the Vietnamese American community especially with those with anticommunist elements. There were very few people going back to Vietnam at that time and I myself had very conservative leanings. My research and my self-awareness of who I am was also an evolution. This is an evolution of a young person to an older person, an evolution of a scholar, evolution of a Vietnamese turning into a Vietnamese oversea diasporic individual. I came to Vietnam very conservatively, very ignorantly about so many things because of the media freeze and the isolation of Vietnam very intentionally by the US—coming, I had certain bias and conservative views. I knew I would only go to Vietnam for research, it wasn’t for tourism or for the thrills. I was going to do this out of academic integrity, but I had to be very secretive about it.

This whole process was almost like a covert operation. I know that sounds funny, but it goes counter to who we are as scholars especially because it’s so esoteric, the things we write, we really strive to get our work out. Building a name for ourselves is really instrumental, but this goes counter against what I needed to do to get information. So I never told people my research. I never told people who I was. I was asked to do interviews all the time to create a bridge or to be critical of the government. All sides were seeing how they could manipulate and use me as a propaganda tool. I declined. I never agreed to do pictures with any flags. I was doing a covert research operation for twenty years.

It was only when my book came out that I whole-heartedly had to own it, that I’d allow for things like this interview because at this point to keep it a secret would be kind of asinine. I’ve already committed, my name is all over the book, my criticisms, my views, my analysis, my ethnography—it’s blood, tears, sweat all in there and I wholeheartedly own my scholarship. When I have the opportunity to talk about this, I am now very, very open.

Your book came out in October, but have you received any criticism against it?

Now there seems to be great interest. I’ve had quite a few book talks and interviews. It’s very quick as you know these things take two to three years, but there is this urgency in wanting to be the first to review my book; I feel there’s an interest because of the nature of the topic as you pointed out.

My initial impression was that anticommunist groups within the community would absolutely hate it and hate me. In Vietnam, it would be the same because I am critical of the government and society and the oppression of dissident individuals or anybody. I don’t know how the community is taking it, but you know, as I talk about in my book, community is really broad. I think for the majority of the community, especially the intellectual group—they can be activists and so forth—they really embrace this research. Anticommunists– not so much, but people have been telling me it’s due in part to language so once and for all, hopefully, if my book is translated there will be time enough for them to hate me!

In Vietnam, however, I found it interesting that I have been very much well-received by individuals in Vietnam—scholars and government officials and media—I could only think of one reason and that is because even though I am very critical of the government, I also really balance the analysis of the triple domination. In that balanced analysis, I’m critical of other groups too: the US and anti-communist groups along with the Vietnamese government. So the Vietnamese government, they’re used to being criticized, but they’re never used to it being turn at other groups and being treated in an equal way. They view my work as extremely balanced in comparison to this rabid criticism of everything about Vietnam and the Vietnamese government.

I’m surprised there, I’d have to say. In some ways, I feel sorry they’re put into a position where any little fairness in terms of scholarly work they accept because there has not been in the past. There’s been this sort of white liberal “Vietnam is great, it was a revolution, it was legitimate” and all that, and then there’s other earlier, I call them orientalist, writings about the war and so forth. So there’s that very pro-North and pro-government and the vets coming in and talking about that, of course that part they accept.

But I’m overseas Vietnamese. I was born in Vietnam. I represent for them, in some ways, a shift in the possible mindset of the diaspora community which for them is quite crucial. We give $10 billion a year in remittances. We have hundreds of thousands coming back annually for tourism. We give in terms of gray matter or social capital or professional capital to them all the time so obviously, if it has a more neutral or accepting view of their “home country” then it’s beneficial. I think they see me as that someone for the first time represent an evenhanded voice. That’s my analysis anyway. I can’t get into their heads, but they’re out there giving me voice in national media. To me it speaks volumes.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

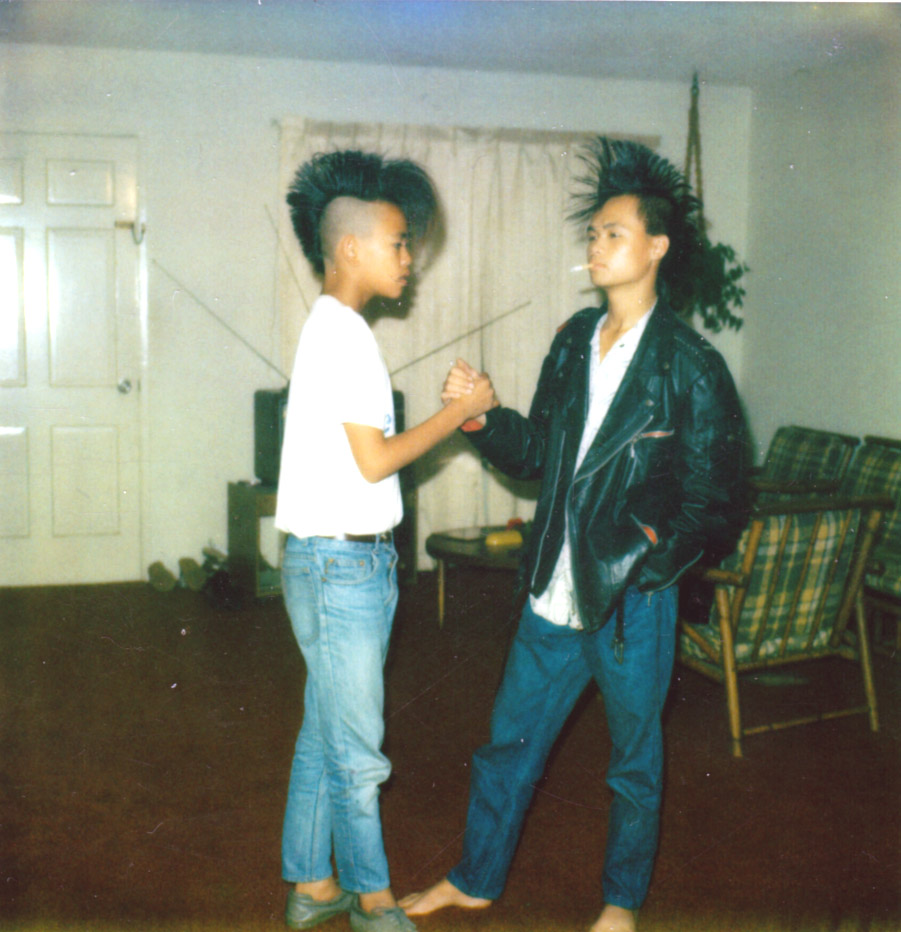

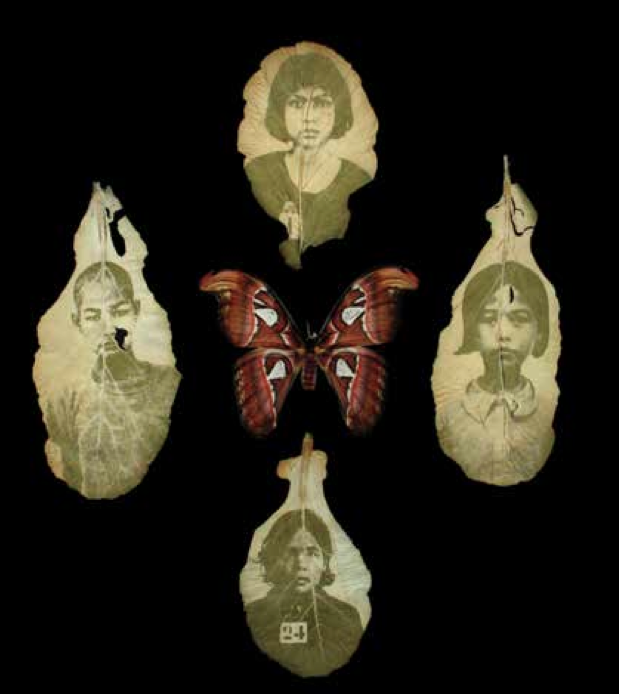

- FOB II protest sign comparing Ho Chi Minh to Adolf Hitler.

You also mentioned in your book that the generation of Vietnamese in the US right now is more free to be not sternly anticommunist. In your book, you mentioned a socialist Vietnamese diaspora group, for example. What do you see Vietnamese American activism and art going towards in the future because anticommunists are losing control in the Vietnamese American community?

I see it as an ongoing battle to be honest. I’m quite surprised, though I shouldn’t be because each year each generation you would think it would wane. Actually, at one point in my research, maybe a decade ago, even more recently, I’m like “Oh my gosh, once my book is out whenever it gets out it’s going be really dated because everything will be smooth out by then.” And lo and behold, it hasn’t!

There are still those groups who are extremely vocal—“Vietnam is still suppressing dissidents.” Anticommunists are still making and throwing things at Vietnamese nationals that come to sing or artists or writers. There’s still that tension that’s so pronounced: whenever there’s an exhibit, everyone is calculating—how much do we show of this kind of work because it could be perceived as communist. It’s a lot of self censorship still.

I think with writers and artists—on the one hand, I see them as soldiers in the front line, making this change overtly and covertly. On the other hand, I see them being—because they’re in the front of the line—the first to be attacked. In this, I include bloggers and any other form of expression. It is so important on both sides to control cultural production and I mention that extensively in my book; it becomes a battle for identity and representation in culture in Vietnam and the diaspora. So the arts become really pivotal in this cultural war, and it’s sad because—you’re an artist, you’re a writer, you understand how important it is to express ourselves and how important it is to advance the arts and it feels so many times stifling when one has to live under this state of fear and self or imposed censorship on all sides.

Then we’d have to become clever about it as artists are in former Eastern European blocs. There are ways language is used an interesting way or art is done in interesting ways—so we do that. Or we take action and get beaten down in battles then come back up. But I want to say it is an exciting time, too because artists are soldiers for change and representation.

Even myself, I feel like I’m academic and yet I’m putting myself in this political situation. It’s kind of exciting because you feel like you’re taking a stand so your actions become very bold and in some ways empowering or you choose to be silent or you choose to do it behind the scene, but all these things are very methodical: the art becomes multilayered. That’s my take on it. I don’ know if that answers your question. But I think it’s tension-filled and exciting and creative on the one hand and potentially stifling on the other hand.

My final question would be what’s next for you as a scholar, as an activist. Your book is a wide range of subjects: you cover pop music, internet forums, politics, art. What’s next for your research?

Simultaneously, as I’ve been working on this book for 20 years, I have been looking at representation of women in Vietnam: how it’s translated in the diaspora, how these representations are sort of perpetuated by native and non-native scholars, writers, policymakers and so forth, and how it creates certain mythologies around Vietnamese women that have been really detrimental especially in terms of recent current events and state of affairs around gender politics and gender issues in Vietnam—anything from the sex trade to political representation, etc.

It’s really similar to my first book in that again it will probably put me in an unpopular light because I will be tackling two stereotypes: one of Vietnamese women as warriors and the other as martyrs. On the surface, these are two very positive things that males and females in the diaspora embrace as a trope and as a belief or philosophy around gender. But I’m here to really put a monkey wrench in that and say that it’s fabricated and it’s perpetuated and it’s detrimental for the future of gender rights in Vietnam and diaspora. It’s a very political move, one that’s seeped in literary criticism, but also very much doing an interventionist project and what’s going on in society right now. Again, offering information so people can decide what they want to do with that.

My third project, or what I’d like to call my third book, is looking at what I call national aesthetics and it’s this idea of nations making and remaking themselves through aesthetic production. This is the work I’ve done previously around áo dài as national symbols and cultural productions. My background is also in political science, so I’ll look at nation building. I’m very excited about that project. My second project is one that has been with me for just too long—like 15 years—I really need to get it out. The third one I feel like there’s room for new research there. I’m very excited about that. Those are my projects for the future.

I’m really glad to get this one out. It’s like long labor: I’m glad it’s delivered. I really tried to do a paradigm shift and I’m hoping that will be an impact in that it will change the way we look at history…We’re not just boat people coming here and resettling and then putting up our 3 striped South Vietnamese flag. We’re much more diverse and there’s so much more around our agency and our sheer will to connect to other people and each other in diaspora that needs to be really put out there because that’s really the vast majority of us.

Professor Kieu-Linh Caroline Valverde received her B.A. in Political Science and Ph.D. in Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. Her teaching, research and organizing interests include: Southeast Asian American history and contemporary issues, mixed race and gender theories, Fashionology, Aesthetics, Diaspora, and Transnationalism Studies. She authored Transnationalizing Viet Nam: Community, Culture, and Politics in the Diaspora (Temple University Press 2012). This book explores the immense influence of the native and diasporic communities on each other in politics, culture, community, generations, gender relations, technology, news media, and the arts. Professor Valverde founded Viet Nam Women’s Forum (1996), a virtual community with over 300 women globally, and Our Voice (2008), a consortium of concerned Overseas Vietnamese that puts forward ideas and action plans that best represent their communities and promote development globally (2008). Professor Valverde was a Luce Southeast Asian Studies Fellow at the Australian National University (2004), Rockefeller Fellow for Project Diaspora at the University of Massachusetts, Boston (2001-02), and a Fulbright Fellow in Viet Nam (1999). As a passionate advocate for the arts, she curated the exhibit Áo Dài: A Modern Design Coming of Age (2006) for the San Jose Museum of Quits and Textiles in partnership with Association for Viet Arts, and consults for the annual Áo Dài Festival held in San Jose (2011, 2012).

Eric Nguyen has a degree in sociology from the University of Maryland along with a certificate in LGBT Studies. He is currently an MFA candidate at McNeese State University and lives in Louisiana.

Would you go back to Vietnam–pre-1995–to perform research before the regularization of diplomatic ties? What would you risk for the sake of pure scholarship, art and knowledge?

Please take the time to rate this post (above) and share it (below). Ratings for top posts are listed on the sidebar. Sharing (on email, Facebook, etc.) helps spread the word about diaCRITICS. And join the conversation and leave a comment!

please like, share, and comment on this post! Interview with Kieu-Linh Caroline Valverde: We’re not just boat people